Chapter 10: Longstring Tillering

Up to now we’ve just roughly floor tillered. I also like to do a lot of this early stage tillering in a vise. Or you can simply pull your bow manually, ideally in front of a mirror or a camera.

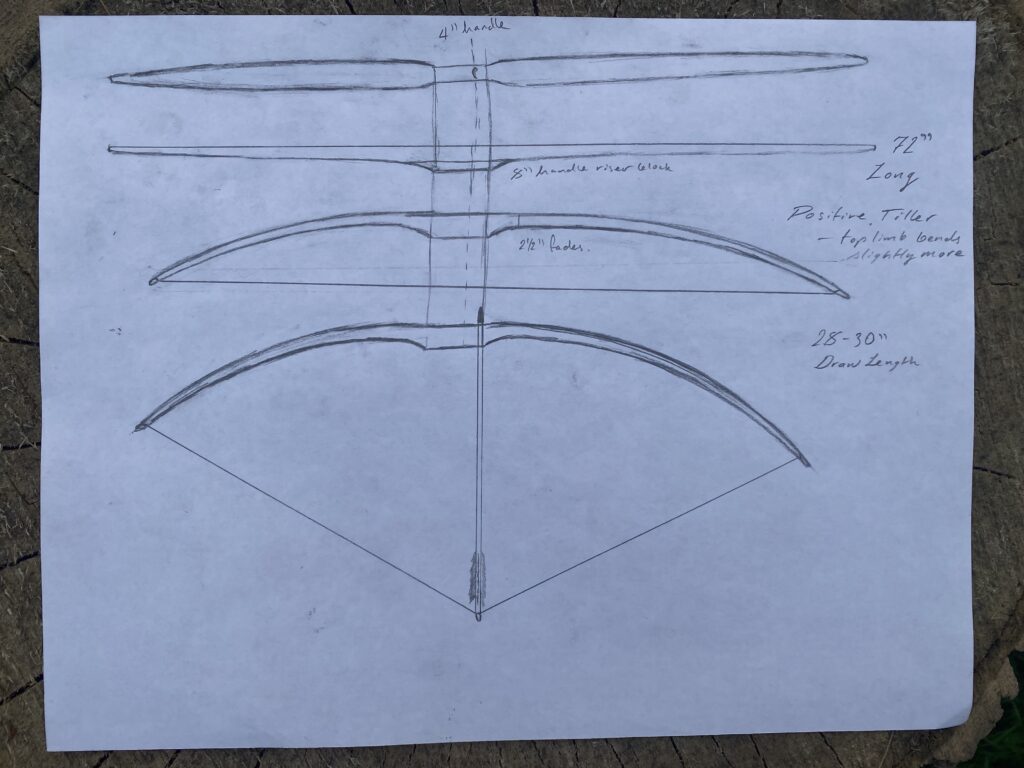

The profiles of the bow influence the ideal tiller shape. In other words, there’s not a universal perfect tiller shape that applies to all bows.

For this design, and straight stave bows in general, a perfectly tillered bow will have limbs that bend in an elliptical shape. Sometimes that’s a circle, sometimes a more eccentric, stretched out ellipse. Which ellipse is exactly right for each of your bow’s limbs is a bit of a judgement call.

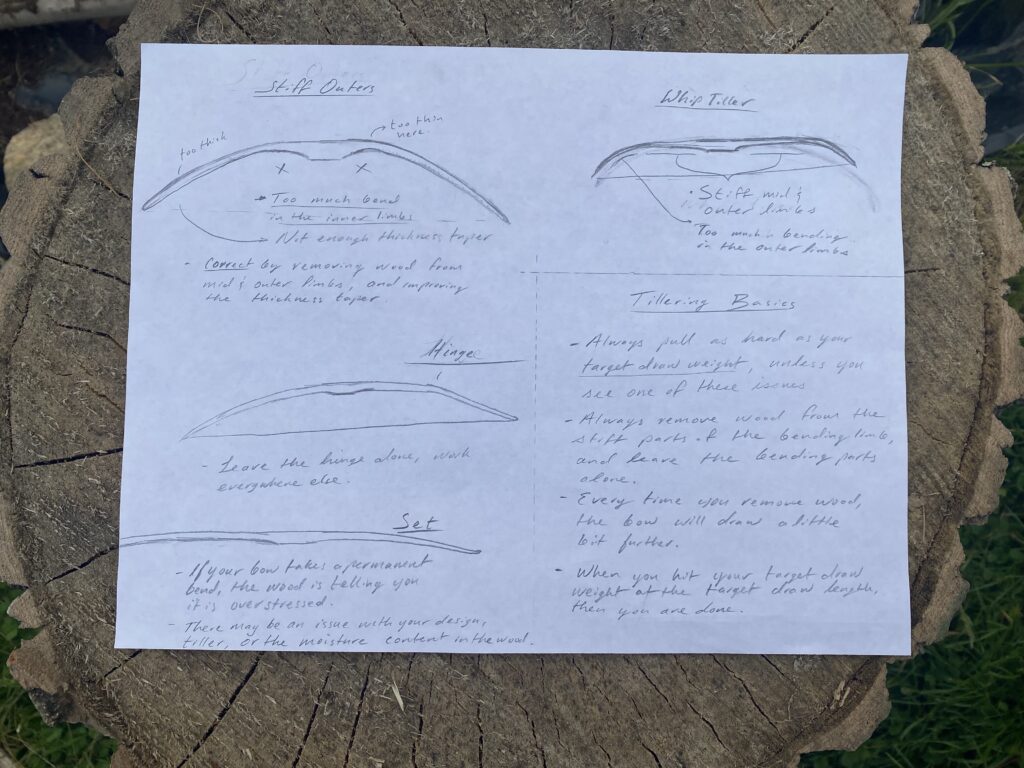

Common Tiller Issues

Here are some common tillering problems you’re likely to encounter, and how to work through them.

1. Stiff outers. Characterized by too much bending from the inner limbs and occurs if you don’t taper your limbs enough. Correct this issue by scraping wood from the mid and outer limbs. In bad cases, you’ll have to go back to the rough out stage to correct the thickness taper.

2. Whip tiller. This is the opposite of stiff outers: a whip tillered bow has outer limbs that bend too much. Correct this issue by working the inner and mid limbs. A whip tillered bow can be very sweet shooting in a mild case, and isn’t as harmful if you shoot light arrows, but in general this tiller shape will cost you some efficiency.

3. Hinges. If you remove too much wood from any particular spot, it will bend too much and might start to hinge. If you let a hinge develop too far your bow will break, or at least take a lot of set in that spot. If you catch a hinge early, save the bow by removing wood everywhere else. If you encounter this issue it may be a good idea to drop the target draw wight

4. Set. A permanent deformation in the wood due to bending. This is a sign that you’ve overstressed the wood because it’s too moist, or there’s a design or tiller issue. For more about set, string follow, and heat treating see Chapter 12.

Tillering Basics

- Try to always pull with roughly the force of your target draw weight—unless you see one of the tillering issues above.

- Always remove wood from the stiff parts of the limb, and leave the bending areas alone.

- Every time you remove some wood, the bow will pull a little further. When you hit your target draw length at the target draw weight, then you’re all done.

Before we go back to tillering, I’ll just touch up the fades a little bit. This will slightly lengthen the fades, and ensure that all the bending stays away from the glue line in the handle.

Don’t take off so much wood that the inner limbs get thinner than the rest of the limb. The inner limb should be the thickest part, and the thickness should decrease smoothly all the way from the fades to the tips.

Make sure you have a good thickness taper before you tiller. If any spots get thicker as you go from the handle to the tip, address those now, before you move on.

Longstring Tillering

Since the bow isn’t ready to brace, we have to tiller it with a longer string. Personally I like to longstring tiller very late into the process, but some bowyers brace the bow as soon as they have the chance.

Every bow is a little different to tiller. Here’s the play by play for this one. To simplify I’ll be keeping the top limb always on the right side. For the best explanation watch the video.

Starting off, Im seeing too much bend on the right limb in the inner third. If I keep removing wood from that spot, I could potentially see a hinge develop. Otherwise, both limbs are stiff in the mids and outers.

Next, I scrape or shave some wood everywhere I thought was stiff, leaving alone the areas I noticed bending. Roughly 20 scrapes a side will do, or a few grams of wood. A little more during early tillering and a little less in the final stages. Better to scrape less and check the tiler more often, rather than make a hasty mistake.

Looking better, but there’s still a little too much bend in in the inner limbs. Next I’ll focus on the top limb mid and outer limb.

5 Ways to Assess the Tiller

How do you decide which areas are stiff, so you know where to remove wood? There are a 5 methods I use, each giving their own second opinion on the tiller.

The first is obvious, it’s the shape of the tiller, and how the bow moves on the tiller tree. This is the most widely used input on where to remove wood next, but its also fallible. The ideal tiller shape depends on the front profile and the side profile of the bow, so you can’t just look at a tiller shape and know if its good or not, you need more information to make a comprehensive evaluation.

The second method to get an opinion on the tiller: check the thickness taper. You can sight down the limb to get a visual sense of the taper but there’s nothing like using your fingers as calipers. Very gently pinch the limb—very gently, you barely want to touch it. Then slide your fingers along the limb like a scanner. You’ll be able to feel things that you can’t see.

When both methods agree on where to remove wood you can be much more confident about where to scrape, without fearing that you’ll create a weak spot. The vast majority of the time, if you have an area where the thickness taper is not aggressive enough (in other words the limb is too thick) then usually that will correspond to an area that looks stiff on the tiller tree. If you only use one method, its easy to misinterpret what it’s telling you. But if two or three methods agree, then you can confidently remove that wood.

Number three: Set. Once again I’ll gloss over this quickly, because set is so important that it’s getting its own chapter. For now—keep track of the original shape of the bow. Any areas that permanently retain the bend are overstressed, and are extra likely to correspond to areas that bend too much on the tiller tree, or seem to get thin too fast in terms of the thickness taper.

Number 4: look at the wobble on the tiller tree. If your bow has a stiff limb it may rock to that side while you pull it on the tree. Some bowyers like to clamp the bow to the tree, or use a wide flat bow mount— both interfere with this method. Putting a grid behind your tree also interferes with this method.

Use these four methods to crosscheck where you should remove wood, and you can tiller much more confidently. Finally there is one more option you shouldn’t overlook, and that’s to ask the community for input. If you need to borrow more experienced eyes, the bowyer community is incredibly friendly and willing to help. Just make sure to post at least 3 pictures. You need the front profile, the side profile, and the drawn picture. I’ll go into more details about that later. If you want my help in particular post on the reddit forum r/bowyer and I’ll drop in when I can. Or post some links to pictures down in the comments section.

Shorten your longstring as much as you can to get the most accurate reading on your tiller and draw weight.

Mervyn Patterson

Hi, congratulations on your full tutorial.It was very well done,easy to follow and understand,one of if not the best tutorial I have seen.Thanks very much I as a amateur bowyer found it most informative but being English my experience is more toward the English Longbow or D section bow.I have had some success with Italian and Pacific Yew.After seeing this I will have a go at a flat bow.

Best wishes Mervyn Patterson UK.

dansantanabows

Thanks Mervyn. In the UK also keep an eye out for Ash, Elm, and Hazel. On facebook there’s a UK bowyer’s group you may want to check out. There’s probably someone close to you who can show you the ropes. There are also several UK bowyers on the other groups and r/bowyer. Good luck and enjoy the journey!

Duke

I am very new at this and can’t wait to start. thank you very much for these easy-to-follow instructions and video. As soon as I obtain the equipment and a good piece of wood I will try to follow your directions.

thanks again and be safe

dansantanabows

Glad to hear it Duke. Hope to see your bow on r/bowyer one day. Good luck and feel free to post as many tiller checks as you need

Gingdah

I enjoyed the detail that you have. This one of best Detail videos on making a bow I seem.

Tyson

Picked up a red maple board and a draw knife today, getting started this weekend. Can’t thank you enough!

dansantanabows

That’s awesome! With red maple I’d go for a slightly wider bow than I have, maybe 2” wide, or a slightly lower draw weight of 30 or 35 pounds. Next time if you can, try to get one of the maple species categorized as a ‘hard’ maple like sugar maple. Silver and red are a bit less dense, but don’t worry and it won’t stop you from making a bow. Just pay extra attention to the set and drop off the draw weight if you start seeing more than a couple inches.

Good luck and feel free to post as many tiller checks on r/bowyer as you need

Tyson

Thanks, Home Depot was my first stop for lumber, red maple was the best they had in hardwood planks at the moment, excluding mahogany. I did notice the porousness so went with the best most dense board I could find. I’ll post my progress!

Terry Bowmam

I am not able to get bow wood boards around here to sort thru.

I can get Black Walnut or Eastern Red Cedar bow making lumber, but requires a backing. I don’t want to waste my hickory backing yet, been a long time simce I made a wooden bow.

My question is, will that linen backing in your video be strong enough, with some reflex? Or maybe double it?

Thanls

dansantanabows

I’m not a big fan of doubling up on the backing because of the extra mess and glue line. Better to use a thicker backing from the start. I think with ERC lumber you’re probably going to need a hard backing unless you find a miraculously clean and straight board. With natural staves, if you’re able to chase or almost chase a ring then ERC can handle being unbacked, despite the popular advice. The problem is that the other popular advice for ERC is that it’s ok to violate the fibers on the back. This is only true to an extent and I wonder if this practice has much to do with juniper’s reputation for breaking in tension.

John Halverson

You would NOT be wasting your hickory backing on an Eastern red cedar board (so long as the board is fairly decent grained with few or no knots). In fact, Hickory backed eastern red cedar (often called HERC) is considered a superior combination for high speed, high efficiency bows.

dansantanabows

I will write more in the future as my formal ideas develop. My informal ideas are easily found on r/bowyer. Thanks for this backhanded compliment, I think.

Pat

I’m impressed, I must say. Seldom do I encounter a blog that’s equally educative and amusing, and let me tell you, you’ve hit the nail on the head.

The problem is something which too few people are speaking intelligently

about. I’m very happy I stumbled across this during my hunt for something concerning this.

Kevin

G’day Dan, fantastic tutorial. I have always wanted to make a bow and I would like to thank you for putting the time into your channel. I live downunder and I am trying to work out what local timber I can use. After watch this I think I will try to practice on a fine grained timber and will certainly look what is in town at the hardware as well. Thanks again. Cheers Kev

Rex

G’day Kevin, I’ve heard quite a few say Spotted Gum is a good option of you find a nice board. I couldn’t find any it the right size at my local timber supplier so I opted for a really straight bit of Jarrah as it’s properties looked similar to hard maple (density, elasticity and modulus or rupture), hopefully it will work. Some others have said iron bark could work for a bow, but that stuff is so hard it makes it difficult to shape.

Rex

G’day Kev

I’m keen to try this out as well. I’ve heard Spotted gum is a good option. I’m going to try it with some Jarrah. Ironbark might work but that stuff’s really hard, shaping it will probably be a pain and lots of tool sharpening.

Cheers,

Rex

Rex

G’day Kev

I’m keen to try this out as well. I’ve heard Spotted gum is a good option. I’m going to try it with some Jarrah. Ironbark might work but that stuff’s really hard, shaping it will probably be a pain and lots of tool sharpening.

Cheers,

Rex

Mickey O'Neill

Dan–My son and I have decided at the same time to get into traditional bow-making. We shot off and on for years, and really enjoy being out in the fresh air and sunshine losing arrows together!

We both truly appreciate your teaching style and the beauty of the videos you’ve made. Thanks for your generosity!

We both went to the store and got red oak boards for our first bows. That is some hard wood! It’s pretty slow going for the moment, but we’ll see how it goes as we progress.

We share the ultimate goal of crafting character bows out of wood we harvest for ourselves. We’re in Oklahoma, and tried over 20 years ago to make a bow from a piece of Osage Orange. Our attempt still hangs in my office! Hopefully, with your tutelage, we will produce something that shoots!

dansantanabows

Good luck Mickey! I heard from your son on reddit last week and am very glad to hear you’re taking on the project together. Let me know if you have any questions or trouble, and feel free to post as many tiller checks on reddit as you need. Go make a bow!

Ross H

Dan, I loved this tutorial. Extremely helpful, a friend of mine and bowyer, Correy Hawk pointed me to your video. I had a question regarding the scale of the bow.

If I wanted to follow your tutorial to make a kids bow (for a 3-5 year old) how does this scale down from the longer ones you make?

Thank you.

dansantanabows

Correy is an awesome bowyer and teacher. I would love to film one of his classes someday. To answer your question it depends a lot on the design. The absolute easiest way is to copy other kids bow’s dimensions that you see on other forums. Of course you can only copy the rough out dimensions since the true dimensions will be revealed by tillering. For a same length bow you can adjust the draw weight by scaling the width. And as a rough rule of thumb you can estimate the bow length by doubling draw length and adding on the length of your stiff handle, and adding a few extra inches per limb for stiff tips. This will give you plenty of margin for error. It’s possible to make a bow shorter but that will give you a nice safe length.