Chapter 5: Backings

What do you do if your stave or board does not have a clean strip of fibers across the back? If it’s an otherwise good enough stave, you could chase a growth ring, but that’s not always possible due to the growth ring orientation. The other option is to add a backing.

Backings fall into 3 general categories. Soft Backings, hard Backings, and sinew. When you add a backing, you no longer have a self bow: now you’re building a simple composite. For the most part my interest in bow making revolves around self bows, and personally I find that adding a backing ruins the experience, and the wholesomeness of a self bow: a bow made from one piece, a bow made from itself. If you ask me, the best backing is air: it adds no weight and lets the wood shine on it’s own. Now that’s just my taste in bows, which is not what this piece is about. So let’s get to it:

Soft Backings

Functionally, bows with a soft backing are very similar to a self bow, generally speaking. You can add a soft backing at any stage of the process while you’re making a self bow, and it shouldn’t massively change the design, function, or draw specs. Soft backings don’t add a huge amount of tension safety: just a little bit of extra margin for error. They do however excel at protecting the back of the bow from scratches and dings.

Rawhide is the quintessential soft backing: it’s extremely tough, dries hard, and works well with hand tools. Plus it can be applied with simple wood glue. Cloth is also a very popular backing choice because it’s so widely available and so many different fabrics are useful for backing. My go to recommendation is thick linen, but you can also use denim from old jeans, or just about any other tough cloth you find in sheets, old clothes, dress ties, etc. You can also apply cloth with wood glue. For an example of how to apply a cloth backing but that also applies to any soft backing: see chapter 6 of my board bow buildalong. Also very popular are plant fiber backings, including raw peeled or combed fibers from plants such as flax, hemp, or brambles, as well as thread made from similar plants, especially hemp and linen.

When it comes to backings, there are many I recommend avoiding. Fiberglass cloth is a popular choice, but personally I don’t recommend it because its a pain to work with and it’s so rigid that it can overwhelm the belly of a bow and exacerbate set. In my opinion wood bows don’t mix well with fiberglass. If you’re going to back a bow with fiberglass, you may as well make a proper fiberglass bow (with fibersglass laminates on both the back and belly.) A wood belly can’t stand up well to a fiberglass backing without getting overwhelmed and taking set. There’s good reason in my opinion that fiberglass backed wood bows came and went very quickly in commercial archery history.

There are also a few backings gaining popularity that I consider to be fun gimmicks for entertainment value, but not actually worth using. Just because they CAN be used, doest mean they’re doing much useful work. These include fiberglass drywall tape and rawhide from dog chews.

Fiberlass drywall tape is a very popular backing for board bows but I don’t recommend it because it’s not very good looking and doesn’t even offer much in the way of protection. Often it’s applied in more than one layer, leading to sloppy craftsmanship and meaning that there are now multiple glue lines to fail, rather than just one. I’m obviously going hard against drywall tape in part because of taste, but it’s also just lousy backing. Most types of cloth will look better and offer the same protection, without the risk that fiberglass has of overwhelming the belly.

Another popular choice I recommend avoiding is rawhide from dog chews. Not all rawhide is ideal for bow making. You want thin stuff that has only been dried and stretched—not exposed to heat, and not tanned into leather. Rawhide for dog chews is way too thick and heavy, plus its been cooked making it bubbly, porous and much weaker. It also comes in small strips, and so you may have to overlap several pieces per limb. This stuff bears very little relation to proper rawhide used for bow making, and I see no reason to use it over whatever cloth you probably already have lying around.

Next up are hard backings: I’ll only gloss over this because now we’re really getting away form the sort of bows I make.

Hard Backings

The major difference with a hard backing is that you can’t just add one whenever you want—you use a hard backing to assemble the stave or the bow blank that you’ll start off with. Hard backings are typically very thin strips of wood or bamboo, pressed and laminated onto either a core or the belly wood. If I talk too much more about hard backings Ill definitely overextend my knowledge: this isn’t the type of bow I make.

Sinew

In some ways sinew is like soft backings; it’s soft when you apply it and can take the shape of the back of the bow. You can also apply a thin layer of sinew at any point in the construction without massively changing the design. Thicker layers however will have a big impact:

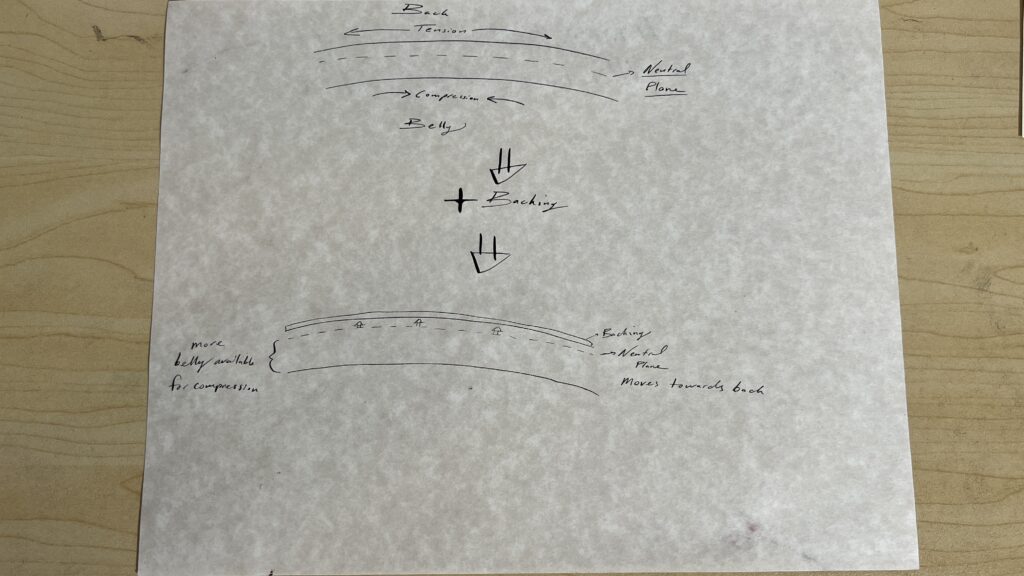

As sinew dries after being applied, it shrinks, and pulls the bow into reflex. This moves the neural plane of the bow closer to the back. The neutral plane is the strip in between the back and the belly which is neither under tension nor compression, but in a neutral state. When you bend any piece of wood, the back will go into tension, and the belly into compression, and the two forces go into an equilibrium state at the neutral plane. When you add a backing, particularly sinew, the neutral plane moves closer to the back of the bow, because not as much wood is needed along the back, now that a backing has been added.

The surprising and interesting effect of moving the neutral place closer to the back of the bow, is that this leaves more material on the belly side of the neutral plane, effectively making the bow better able to handle compression. Counter intuitively, adding a backing has strengthened both the back and the belly.

By the way, this only works if the backing material is sufficiently flexible. If the back of the bow is too stiff this can result in extra set. You’ll see this if you add an overstiff backing like fiberglass, or even in naturally tension strong woods like hickory and elm, which are so tension strong that the belly can’t keep up.