Chapter 4: Decrowning

If you merge two previous methods: the natural back, with the board bow approach: you get decrowning.

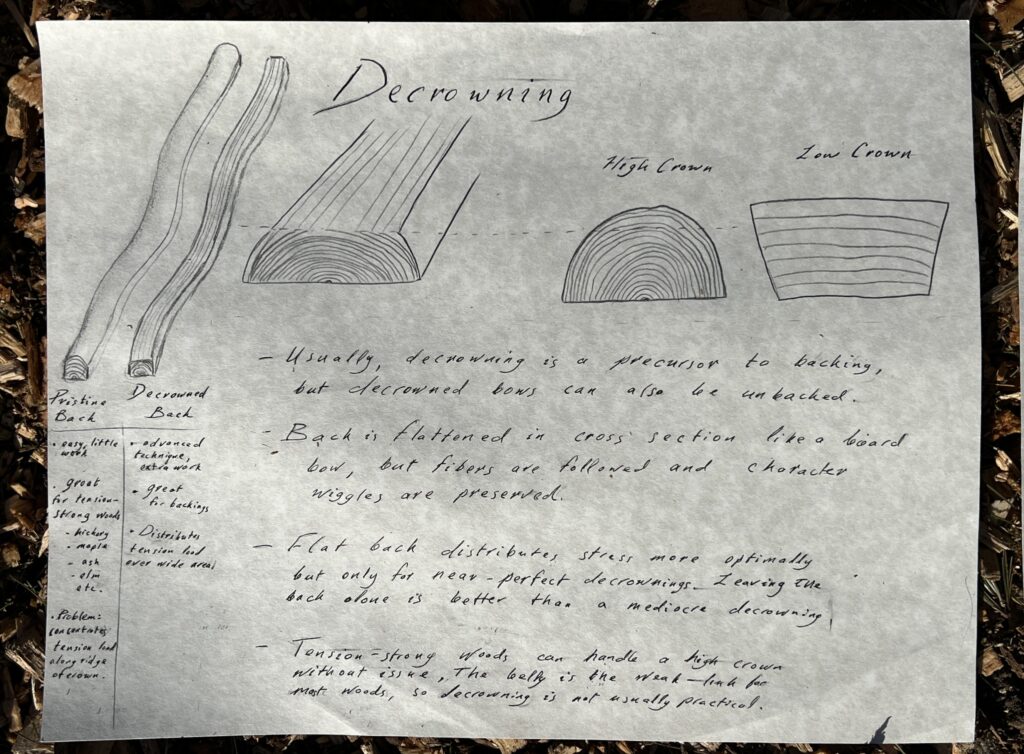

The crown is another term for the curved surface on the outside of the tree. Low diameter staves like saplings will have a relatively high crown, while staves from large diameter trees will have a relatively flat crown.

Decrowning is the act of flattening the crown on the back of the stave, so that it resembles the back of a board bow. This is almost the same as turning your stave into a board, except you’ll be able to follow all the bends and wiggles in the wood. In other words, much like a board bow, a decrowned bow has violated growth rings, yet a back that is unviolated, because the fibers that run across the back will be entire and uninterrupted.

As a result, you don’t have to be as selective about using perfectly straight grained wood like you have to with a board bow. For a perfectly straight stave, decrowning or making a board will have almost the same result. But for character staves, you can now have a perfectly flat back in cross section, without having to violate the fibers, or introduce runoff by ignoring the wiggles on the side.

All this begs the question of why you would even want to do this. The most common use of decrowning is as a precursor to adding a backing. We’ll get back to that in the chapter on backings. For now let’s stick to self bows.

The issue with a high crown is that it concentrates the tension stress along the peak of the crown. In other words, the ridge along the center of the back does more than its fair share of work, and the rest of the back is potentially dead weight. That’s the argument anyway. I rarely ever find myself in a position where it’s worth the trouble.

Most of the wood species I use are tension strong white woods such as hickory, maple, ash elm etc. These woods are so strong in tension that in most cases it’s hard for the belly of the bow to keep up. Many bowyers actually trap the back with these species, ‘trap’ being short for trapezoidal cross section. In other words, trapping is to narrow the back.

This might seem counter intuitive if you’re only just beginning to make bows—in that case tension safety tends to be the number one priority. Before you worry about performance, you need to make sure your bow can stay in one piece. With a bit of experience designing and tillering bows, tension safety stops being the primary concern in most builds. If you implement the methods in this guide, you’ll have a back that’s plenty tension strong, and so the belly becomes the weak link in the design. When the wood gets overwhelmed, it begins to take set, and this primarily happens in the belly. (If you’d ever like to verify this saw a bow with set along the neutral plane and watch the back spring back into the original state, while the belly retains the set.)

If you think about it, trapping and high crowns are conceptually very similar: they concentrate the tension force along a narrower strip of the back, resulting in a wider belly than back. So if trapping is advantageous for tension strong white woods, then a high crown should at the very least be fine, and at best maybe even advantageous. Some of the very best wood I’ve used comes from small diameter stock with a high crown, and I almost never feel a need to decrown.

I’m not saying that the practice of decrowning is nonsense or that it should never be done, I just don’t find it to be worth the risk most of the time, for most of the wood I use. A pristine natural back is very valuable to me, and it’s very very hard to decrown to the same level of precision. It’s absolutely true that decrowning can potentially increase tension safety, but keep in mind that this assumes you’re skilled and patient enough to perform a perfect or near perfect decrowning. Easier said than done.

If you also mostly work with tension strong white woods like I do, I recommend that you ignore the very popular advice to decrown low diameter staves. In fact, I highly recommend low diameter staves because they’re easier to find and involve less labor in wood removal. Again, there may be advantages to a perfect decrowning, but whether the risks are worth it are another matter. For woods that are not as relatively tension strong, such as osage, decrowning makes more sense, but I still prefer to design around the stave most of the time, opting for the extra assurance that a pristine back gives you.

As I said before, personally I find that decrowning makes the most sense as a precursor to a backing. So let’s get into Chapter 5: Backings.